- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

A recent essay of mine described the Fracking Re-Invasion of Wetzel County,10 years after it began.

When shale gas drilling started here in Wetzel County WV in 2007, it had already been causing problems for a few years right across the state line to the north, in Green and Washington counties in Pennsylvania. (12 years of fracking-related activities in PA have resulted in 9,442 citizen-reported complaints to that state’s DEP.)

The two biggest problems which immediately arose wherever shale forces invaded our lands were the massive traffic caused by shale operations (I’ve been caught in who-knows-how-many cluster trucks over the years), and the overbearing legal “rights” of gas companies with regard to property acquisition and taking.

Now, ten years later, we have begun to address truck accidents and congestion, and the gas company truck traffic is frequently better managed. However, one of the unresolved problems is that West Virginia law grants gas companies what is essentially the power of eminent domain for taking the private property of surface owners. Gas companies want eminent domain because, working on behalf of the mineral rights’ owners, they have an insatiable and ever-present need to get to the gas buried beneath our state.

One of the few restrictions on well pad locations in West Virginia was written into our state law in the Horizontal Well Act of December 2011. That initial attempt for minimal regulations for shale gas exploration and development declared an arbitrary distance of 625 feet from a well-pad-center to an occupied dwelling. That distance is called the setback.

Photo 1, below, is one example of inadequate setbacks at a temporarily completed well pad very close to a home here in Wetzel County, WV. That home to the right is about 80 feet from the edge of the well pad. No one should live there. Ever.

Within West Virginia law, there are very few other constraints on well pad locations. One other such constraint is that well pads must also be 100 feet from streams and wetlands. All these setback dimensions have been continually debated ever since then. Gas companies always want the distance to be very small, and any nearby surface owners or residents wants it to be very big. If there were no legal restrictions, or state regulations, the gas companies would have the edge of their well pads up against your backyard fence in any neighborhood.

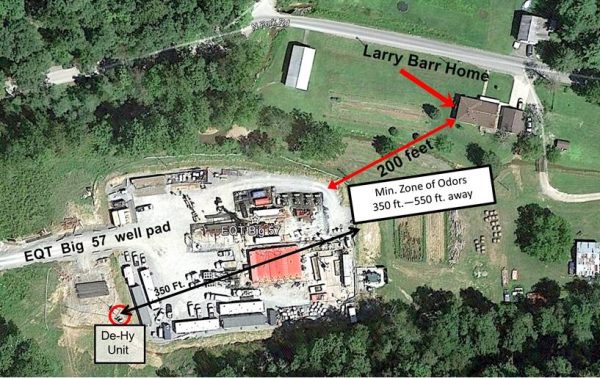

Photo 2, below, shows another example of a well pad less than 200 feet from a residence in Wetzel County. I personally measured this location and from the well pad corner to the home corner was about 175 feet. Photos 1 and 2 clearly show why legally mandated minimum setbacks are needed.

I will readily admit that there are likely many more locations in Pennsylvania, and many other areas here in West Virginia, which have well pads with serious setback concerns. But since I am very familiar with Wetzel County, I would like to explore the setback problem here. For example, the two locations pictured above immediately come to mind. They are here in Wetzel, and I personally have seen and walked on the residential property where the existing pad edge is about 180 feet from one house and about 80 feet from the other. Without hiring a lawyer, neither home owner or surface owner had any rights within West Virginia oil and gas regulations to stop these well pads. (These well pads were initially in a legal location and now are grandfathered in and more wells can still be added). Since this obviously caused complaints, the 2011 law arbitrarily made the 625 feet setback rule. There was no rationale given for the setback distance. It was not reasonable then, and it still is not. Since many well pad dimensions are close to 400 feet long in one direction, the legal minimum of 625 feet still allows the well pad edge to be 425 feet from a home.

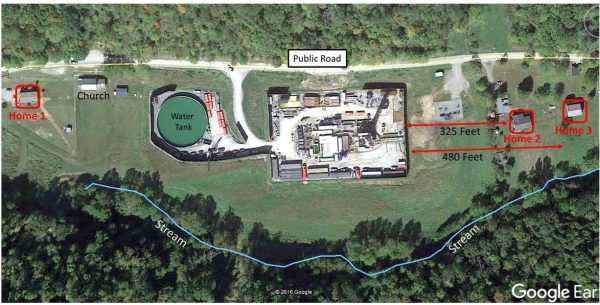

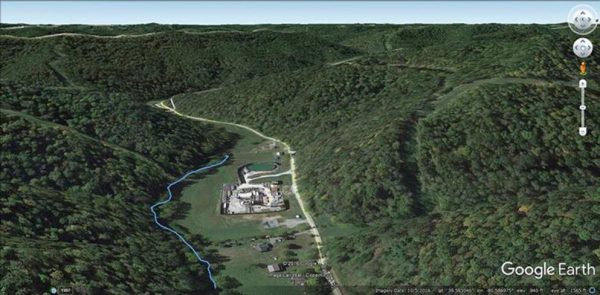

I will only use one location as a good example of a bad location for a well pad. My example below pretty much covers all the problems. It is a very good example of a very bad location of a well pad for many reasons. This Photo 3 was provided in another essay (as photo 5). It has become my poster child for where and why to not put a natural gas well pad. But it was and remains a legal location. I know of other poor locations, and I am sure readers could provide their own worst case example. This one example shows many of the problems all in one place.

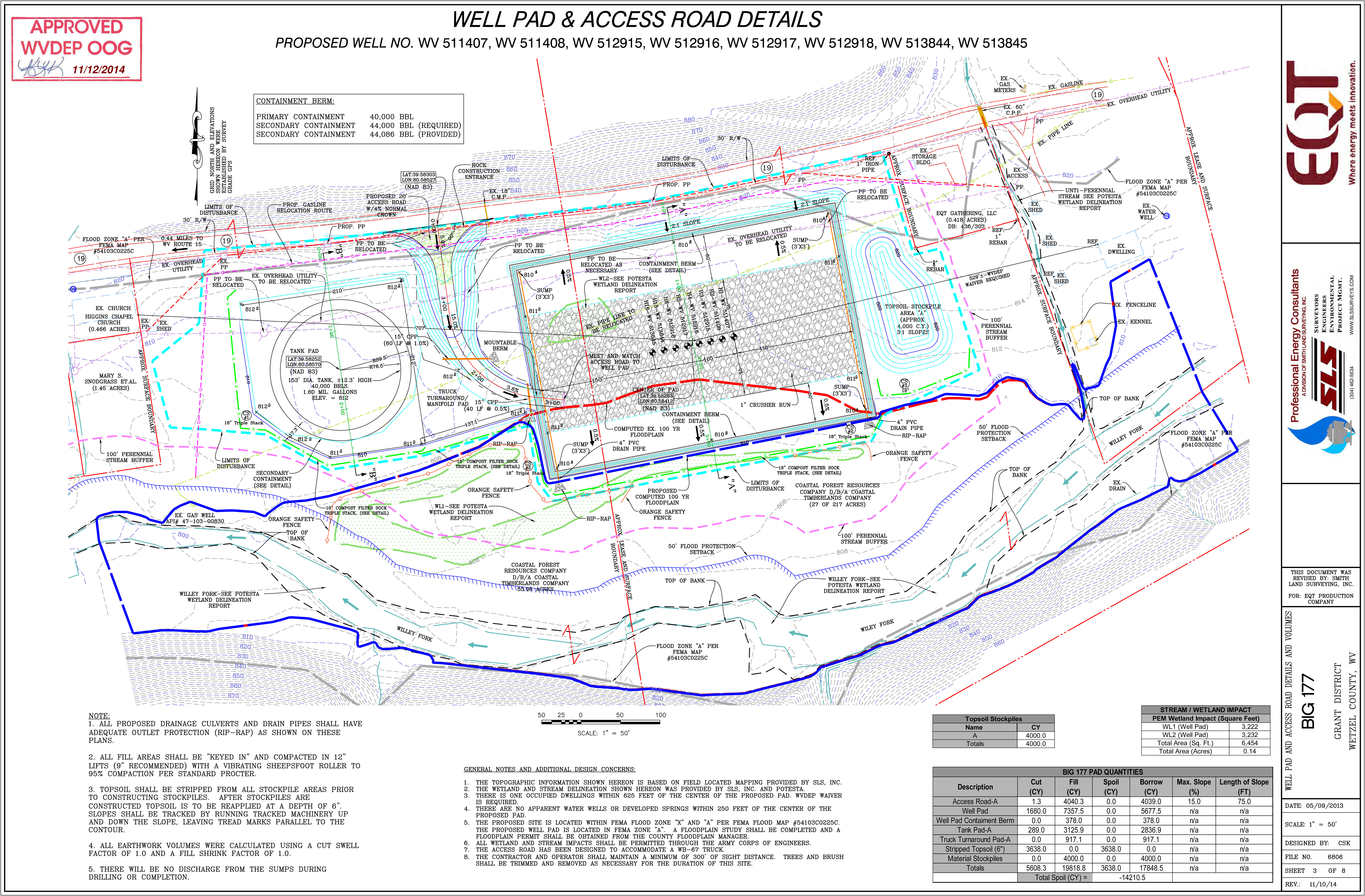

Construction drawing for well pad that became what you see in Photo 3

As you may note, this is a well-designed, well-engineered well pad, constructed in accordance with the engineering drawings, and taking into consideration all the restrictions as listed in West Virginia law. All on the up and up and by the books, yet in a bad location.

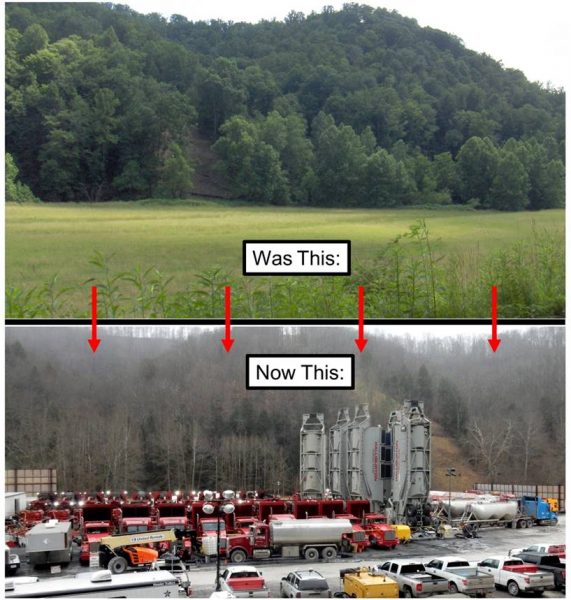

Before proceeding, let us review the previous life of this location. For the past hundred years or more, this perfectly green pasture field was a farmer’s dream, as shown in Photo 4, top. Rich bottom land, bounded by a nearby stream. The area is in a flood plain, and the occasional flooding rejuvenated the soil. And, unlike most of West Virginia, it was close to being flat. Land like that is rare around here, and relatively valuable, at least to a farmer. Why, then, would it be turned into a noisy, smelly, gas-producing, forever barren, packed gravel industrial site? Why? Simply because it was owned by some commercial timber corporation. Timber companies, like gas companies, do not value prime level fields dedicated to agricultural use. Flat fields make cheap well pads. No expensive site preparation needed. So, this land was lush and agricultural, as in the top of Photo 4, and now it has become permanently industrial, as shown in the bottom of Photo 4.

The next major problem with this well pad is the three nearby homes. All three are too close for comfort. But, remember, this is a legal well pad, completely compliant with the minimum regulations and properly permitted by WV Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). But still too close to homes. Let’s see how that can be.

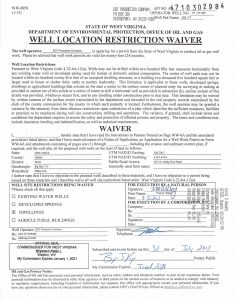

If a driller wants to squeeze a well pad between two homes, and put the center of the well pad closer than 625 feet to one of them, it must have the current owner of the closest home sign a waiver. That was done in this case. The proof of the home owners’ waiver must be provided with the gas well application and it can be viewed here, at left. If you click the image to enlarge it, you can see the a complete list of other well pad restrictions, including those applying to flood plains and wetlands.

If a driller wants to squeeze a well pad between two homes, and put the center of the well pad closer than 625 feet to one of them, it must have the current owner of the closest home sign a waiver. That was done in this case. The proof of the home owners’ waiver must be provided with the gas well application and it can be viewed here, at left. If you click the image to enlarge it, you can see the a complete list of other well pad restrictions, including those applying to flood plains and wetlands.

Due to the problems caused when horizontal well pads are located in residential areas, a similar waiver or legal contract has also occasionally been sought by gas operators in Pennsylvania. Via the contract or easement, for example, the gas company has at times offered $40,000 to the nearby residents to guarantee that the driller would not likely be subject to a nuisance lawsuit, which in turn guaranteed that the nearby residents and future owners would always be assured of plenty of nuisances for the foreseeable future. Click here to review the legal conditions and restrictions that appear in some sample Pennsylvania contracts.

In the local example, as seen in Photo 3, the waiver signed by one home owner might have been arrived at by some financial incentives. However, the next home owner, home 3, thereby was also subject to more noise, light, dust, fumes, and air pollution but received no compensation. But it was all legal because that home was slightly more than 625 feet from the center of the well pad. The folks in this home just have to live with the problems, or try to find a lawyer willing to file a claim against a large gas corporation.

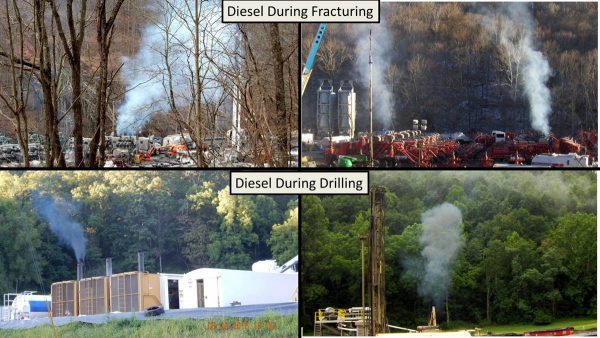

All those who live near an active gas field know there are odors, silica, noise, traffic, damaged roads, runoff, and bright lights that accompany all gas well pads. They are serious concerns, but not the major permanent problem. The foremost problem with homes near well pads (and compressor stations) is now, and for generations will always be, air pollution and its resultant health problems. Diesel fumes are a large part of that in the short run. Shown below in Photo 5 is a sample of the type of diesel fumes that are typically on all well pads during drilling, and then again during fracturing. Try to picture your home next to one of these locations.

I have asked many folks, and I have never found anyone who would be willing to live near this type of air pollution. Diesel exhaust fumes have a nasty track record in public health studies. But some of my neighbors have no choice in the matter. They live here; this is their home. Some of their families have been here for generations. They are here because many of their extended families are also in the area, or in other cases they moved here purposefully and intentionally, for the peace, quiet, privacy, clean air and water, and many other now rapidly fading fine qualities. They used to like it here. No one wants one of these well pads in their backyard, or neighborhood, this close to their home.

To make matters worse, there is a more serious problem with this particular location. Photo 3 and 4 above and Photo 6 below all show the same well pad location from different perspectives. All the homes and the air pollution source are in a deep valley. That greatly compounds the problem. The view seen in Photo 6 is a higher altitude view whereby we can now see the long, deep valley.

If you look closely, you can see the homes, the well pad, then the round water holding tank. But what is important is that the hills are about 500 feet higher. In settings like this, there are two common meteorological forces which influence air masses. First, it is normal to have temperature inversion layers which trap air in a stagnant mass. That means that whatever nasty and dangerous fumes are there, they all lay and stay in the valley. Second, there are conditions with warm days and chilly nights when the dropping temperatures cause the colder heavy air to sink, and it will slowly crawl down the valley, moving any air pollution with it, whether it is diesel exhaust fumes or the volatile organic compounds that come from dehydration plants or condensate storage tanks.

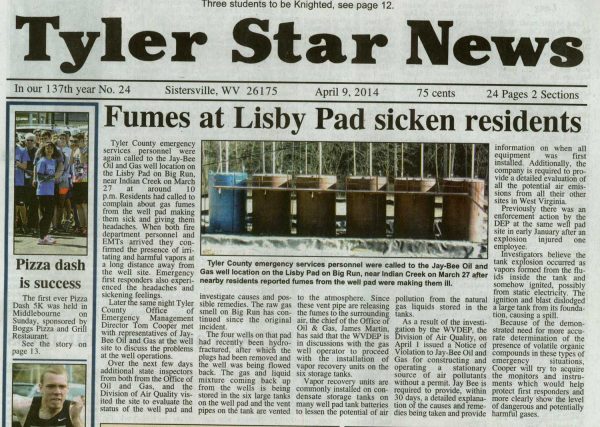

The hazardous fumes fill the valleys, surround the homes, linger for your children and grandchildren, and refuse to leave. These inversion can happen in any hollow in West Virginia, as these well pad neighbors in Tyler County know all to well:

Many a rural West Virginian has seen these inversions at this time of year, if they or their neighbors heat with wood. On many a cold day, in late afternoon when the wind dies down, and the air becomes still, the smoke does not rise. It just hangs in the valley. This is what we see in Photos 7 and 8.

Or it might look like this, Photo 8, below. Now, the smoke or combustion products from wood stoves is relatively harmless compared to the oxides of nitrogen and benzene and the other hazardous air pollutants like the BTEX group also referred to as VOCs, or volatile organic compounds. These are benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, and xylene. You do not want to breathe these in. But you will usually not be able to see them. At least wood-stove smoke gives you a visible sign. You know where it is and where you need to move to avoid it. The dangerous air pollutants from all the many processes required to extract shale gas are invisible, give minimal warning, and are the most harmful.

In many valleys around here, there are all kinds of operations associated with gas development. These include drilling, fracturing, and gas processing on well pads; tri-ethylene glycol (TEG) dehydration plants; pipeline venting; hundreds of atmosphere-vented condensate tanks; and diesel engines by the thousands. Some of the environmental problems like these were addressed in a report done by WVU more than three years ago. Review excerpts from the study and read the entire study itself here.

Over the years, at these types of locations, I have personally:

- Seen gas fumes visibly released from a well pad storage tank for nearly an hour;

- Smelled fumes from multiple TEG dehydration units;

- Watched fumes come out of condensate tanks;

- Known of residents driven from their homes in a valley due to gas fumes;

- Seen, smelled massive amounts of diesel fumes from all the engines;

- Seen gas being blown out of pig launcher-receiver devices;

- And of course, have frequently seen (and perhaps sometimes even breathed!) billowing clouds of silica.

Conclusion:

Here in West Virginia, we do not measure air quality down to the county level. I will readily admit that no one, yet, could prove that we do have a growing public health issue which should concern us. But we do know there are very large amounts of pollutants being put into our atmosphere that were never, in human history, commonly dispersed here.

The state also cannot say we do not have a public health problem due to air quality. We just do not know, and the state of West Virginia does not want to know. The WV DEP’s Division of Air Quality does not have regulatory power via state law to aggregate all the point sources of air pollution. All gas well pads and compressor stations are only individually permitted, and the total accumulation (aggregation) of all of them is not considered. No one adds up all of the pollution to look at the big picture. We are part of a large public health experiment with live participants. This is not a trial run here. This is for real.

Until there is a comprehensive air quality monitoring program in place which would accurately measure what residents must try to live with, to prove that the level of various regulated pollutants are staying well below harmful levels, in my opinion, no well pad should ever be allowed to be situated in any valley as we have here in the tri-county area. The harmful fumes get stuck in the valley. Residents cannot escape them. The states do not do an adequate job of monitoring the air quality, and the gas industry will always put a well pad anywhere they can. West Virginia does not have the regulatory power to stop every valley from being filled with dangerous fumes.

Can the author of this blog contact me?? Do you live there? My grandfather owned 40 acres there he passed away years ago and an attorney has just now been contacting us tgat since he passed we are now the owners and would like a contract to lease the land to look for gas…