Read part 1 here, part 2 here.

Another catastrophic event occurred less than a year later in West Virginia. In October, 2009, most of the fish and other aquatic life in the 28 mile length of Dunkard Creek were killed by a toxic bloom of golden algae spoiling the area for fishermen and picnickers. An EPA investigation failed to pinpoint the exact cause of the algae bloom; according to a New York Times story in 2011, “the reason for the chemical changes that spawned it remains a mystery.” Although the EPA fined Consol Energy Inc. $6 million for the incident and required them to install a $200 million treatment system, another EPA biologist in Wheeling challenged the notion that mining caused the fish kill. He stated that the death of Dunkard Creek may have been caused by environmental circumstances related to fracking of the Marcellus Shale. Whether Dunkard Creek died at the hands of the coal or the gas industry, the water quality problems caused by fossil fuel extraction are likely to keep on coming if we don’t transition soon to renewable energy.

The importance of clean, safe water hit home, literally, for 300,000 residents of the mountain state, when Governor Tomblin issued a “do not use” order on January 9, 2014. Schools and businesses were shuttered for days, hundreds of people were admitted to emergency rooms, pregnant women were cautioned not to drink tap water for weeks, and 100,000 people experienced symptoms from exposure to a heretofore largely unknown chemical. The 10,000 gallon “spill” of crude methylcyclohexanementhanol (MCHM, used for cleaning coal) into the Elk River 1.5 miles above West Virginia American Water’s municipal water intake, served as a wake-up call to politicians, regulators and ordinary people: (1) don’t take clean, safe water for granted and (2) clean, safe water and economic development go hand-in-hand. Politicians and regulators were quick to blame Freedom Industries, the company that owned of the above-ground storage tank facility (some involved with the company were known felons), for perhaps the “worst man-made environmental disaster of the century.” Sadly, environmental “regulators” appointed by coal-friendly politicians, had been turning a blind eye at that facility for decades. Nor had the privately held water company, WV American Water Company, bothered to find out what potential pollutants lurked so near its single intake on the Elk River.

The importance of clean, safe water hit home, literally, for 300,000 residents of the mountain state, when Governor Tomblin issued a “do not use” order on January 9, 2014. Schools and businesses were shuttered for days, hundreds of people were admitted to emergency rooms, pregnant women were cautioned not to drink tap water for weeks, and 100,000 people experienced symptoms from exposure to a heretofore largely unknown chemical. The 10,000 gallon “spill” of crude methylcyclohexanementhanol (MCHM, used for cleaning coal) into the Elk River 1.5 miles above West Virginia American Water’s municipal water intake, served as a wake-up call to politicians, regulators and ordinary people: (1) don’t take clean, safe water for granted and (2) clean, safe water and economic development go hand-in-hand. Politicians and regulators were quick to blame Freedom Industries, the company that owned of the above-ground storage tank facility (some involved with the company were known felons), for perhaps the “worst man-made environmental disaster of the century.” Sadly, environmental “regulators” appointed by coal-friendly politicians, had been turning a blind eye at that facility for decades. Nor had the privately held water company, WV American Water Company, bothered to find out what potential pollutants lurked so near its single intake on the Elk River.

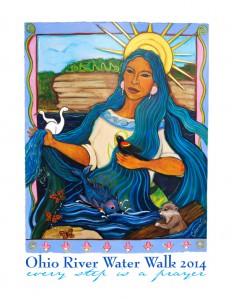

While many people in West Virginia have been concerned about water quality in our state, others across the nation are sounding the alarm. In May 2014, I had the good fortune to take part in a Nibi Walk (Water Walk) for the Ohio River, organized by Sharon Day, an Ojibwe elder of the Indigenous People’s Task Force. As a Midewin, part of her spiritual practice is to care for water. Beginning on Earth Day, she and Barbra Baker-Larush walked the entire length of the Ohio River, the most polluted river in our country. They carried with them water drawn from the headwaters in Pittsburgh, PA, to their journey’s end in Cairo, IL. Many joined them along the way to honor and pray for the water. As a water-woman, Sharon uses these Nibi walks to draw attention to the many concerns around water quality.

While many people in West Virginia have been concerned about water quality in our state, others across the nation are sounding the alarm. In May 2014, I had the good fortune to take part in a Nibi Walk (Water Walk) for the Ohio River, organized by Sharon Day, an Ojibwe elder of the Indigenous People’s Task Force. As a Midewin, part of her spiritual practice is to care for water. Beginning on Earth Day, she and Barbra Baker-Larush walked the entire length of the Ohio River, the most polluted river in our country. They carried with them water drawn from the headwaters in Pittsburgh, PA, to their journey’s end in Cairo, IL. Many joined them along the way to honor and pray for the water. As a water-woman, Sharon uses these Nibi walks to draw attention to the many concerns around water quality.

While water quality is now a major concern, issues of water quantity are also coming to light. I remember hearing back in the 80s that the next war would be fought over water; however, war over water is actually nothing new in this country.

While visiting drought-stricken California in recent times, I noted that the lack of sufficient water was front and center. Since the early 1900s, water has been diverted from the former farming region of the Owens Valley, east of the Sierras, via a highly controversial aqueduct to slake the thirst of an-ever growing Los Angeles population. By 1926, the Owens Valley Lake was dry and little water was left to irrigate crops. Later several attempts to divert water from Mono Lake (north of the Owens Valley) for Los Angeles fortunately were thwarted by litigation. Nevertheless, the people of the Owens Valley still suffer from the loss of their water. Diversion of water is one kind of water war; but cutting off the supply to tens of thousands of people, is yet another. Just ask the people living in Detroit.

In a city still struggling to recover from the largest municipal bankruptcy in our nation, access to water became a human rights issue in 2014. In the 1950s, Detroit was home to 1.8 million people, the same as West Virginia’s entire population. Now it’s less than half that amount, but with shuttered businesses, vacant homes, reduced city services (closed parks and diminished police presence) and a staggering 36.2 percent of residents living below the poverty line (60% poverty rate for children), people are struggling to pay water bills that have increased 119 percent in the past 10 years.

From 1950 to 2011, Detroit’s manufacturing jobs plummeted from 296,000 to 27,000. (Sounds strangely like the decline of West Virginia’s coal industry). In May 2014, Detroit Water and Sewage District (DWSD) sent cut-off notices to 46,000 people when they fell behind in their bills. Combine the loss of manufacturing jobs with the declining population and loss of revenue for the city; add to that an aging municipal water infrastructure, and presto, you have an ever-burgeoning water crisis for many thousand people. The DWDS began cutting water off at the rate of 3,000 customers per week; at that rate, 300,000 people were projected to be without tap water by the end of that summer—another 300,000 people without tap water, approximately the same number impacted by the water crisis in West Virginia. Déjà vu. Apparently while DWDS is cutting off water for individuals, water still ran freely for certain businesses, including Detroit’s flagship golf course, Ford Field and Joe Louis Arena, home to the City’s NFL and NHL franchises, that had not paid their water bills either, but they still received water.

Sadly, for the people of Michigan, the worst was yet to come, when the city of Flint switched their water supply from Lake Huron and the Detroit River to the corrosive water of the Flint River in 2013. As many as 12,000 children were exposed to high levels of lead, a dangerous neuro-toxin, when the city switched intakes and failed to treat the water with an anti-corrosive agent. As a result, the city’s drinking water contained unacceptable levels of lead that had leached from aging water pipes. Between 2013 and 2015, the percentage of children with unacceptable lead levels in their blood rose from 2.5% to nearly 5%. If you are one who thinks that our government and its agencies will jump immediately to correct a serious threat to water quality and human health, think again. The Flint water crisis is a model in mismanagement. For starters, it took nearly two years for the problem to come to be acknowledged. Imagine how much lead contaminated the highly vulnerable bodies of babies, pregnant women or nursing mothers and young children during that time!

Governor Synder did apologize, but how much solace can Flint citizens really take from an apology? Over time, Synder promised to fix the problem with more than $200 million dollars for supplies, medical care and infrastructure upgrades, water bill credits, reimbursements and lead pipe replacements. The water crisis in Flint has resulted in criminal charges, charges of misconduct in office, tampering with evidence, water quality treatment violations, conspiracy to engage in misconduct, and willful neglect of duty. But clearly, neither heart-felt apologies nor millions of dollars after-the-fact can repair the damages that the children of Flint may endure for the rest of their lives.

In the late 80s, I began seeing a few omens that water would become a defining issue in my lifetime, but now issues surrounding tainted water are being reported and incidents of pollution are increasingly frequent, far-reaching and with likely with some long-term consequences . These few examples of recent past and on-going water crises are barely a drop in the bucket (pun, intended). We have mistreated water by our negligence, over-consumption, pollution, diversion, or commodification for the past 25 years. A woman I met once who hailed from St. Louis told me that there was really only one way to treat water, and that was “with great care.”

It really is past time for people everywhere to wake up, stand up for and defend our life-sustaining water.