- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

This article by Deborah Griffith originally appeared on page 20 of the March 2014 issue of OVEC’s newsletter, Winds of Change. Current-day photos here are by Bill Hughes.

The Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster, one of the worst industrial tragedies in U.S. history, has been largely forgotten. But we would be wise to remember it now, because a similar disaster — on a much larger scale — seems to be in the making.

The Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster, one of the worst industrial tragedies in U.S. history, has been largely forgotten. But we would be wise to remember it now, because a similar disaster — on a much larger scale — seems to be in the making.

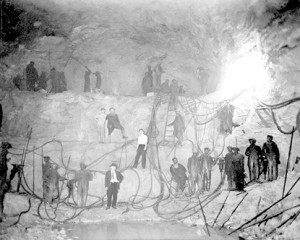

Built mostly from 1930 through 1932, the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel, part of a complex to generate power for Union Carbide’s plant in nearby Alloy, WV, was drilled through three miles of solid rock. It was the largest construction project in West Virginia up to that time, employing about 5,000 workers, 75 percent of them southern African-Americans who had headed north for the promise of jobs.

These men worked in the tunnel only a short time. Because of several circumstances (drilling and blasting in confined spaces, poor ventilation, lack of dust control and personal breathing protection, and seams of exceptionally pure silica), an astonishingly high number of the men contracted acute silicosis, some within two months of entering the tunnel. Hundreds eventually died painful deaths, perhaps thousands.

Silicosis is a progressive fibrosis of the lungs, caused by inhaling pulverized silica dioxide. It is incurable and nearly always fatal. The danger crystalline silica dust posed to underground workers was well known even then, and before work on the tunnel began, core samples were taken that clearly indicated that most of the tunnel would be drilled through high-grade silica-bearing sandstone. In fact, a third of the tunnel was eventually enlarged for silica extraction. But, because the tunnel was licensed as a civil engineering project, even the minimal safety enforcement that was then available to miners did not apply to these workers. However, company officials did wear breathing masks when they entered the tunnel to inspect the work of the unprotected workers.

West Virginia was already in decline before the Depression and so was particularly hard hit. Both coal mining and subsistence farming were devastated early on, and in some counties unemployment rose to as high as 80 percent. Desperate people were willing to work under almost any conditions for almost any wages. In Hawk’s Nest Tunnel: A Forgotten Tragedy in Safety’s History, C. Keith Stalnaker quotes a worker who referred to the tunnel as a “. . . bad job,” but said that he stayed on because, “. . . when you got some babies looking at you for something to eat, you’re going to work.”

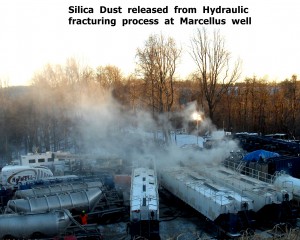

Fast forward to the present, to a depressed economy and high unemployment in West Virginia. Workers in many industries are exposed to respirable (breathable) crystalline silica, which the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) claims kills hundreds of workers and sickens thousands more each year through lung cancer, silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and kidney disease. Among the vulnerable industries are construction; concrete, brick and pottery manufacturing; and our latest natural-resource boom: hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.”

Fracking uses high-pressure injection of large volumes of water and sand and chemicals to fracture shale or other rock formations. Crystalline silica (“frac sand”) is used to hold open the cracks and fissures created by hydraulic pressure. Each stage of the process requires hundreds of thousands of pounds of quartz-containing sand; millions of pounds may be needed overall. The mechanical handling of frac sand creates respirable crystalline silica dust.

Fracking uses high-pressure injection of large volumes of water and sand and chemicals to fracture shale or other rock formations. Crystalline silica (“frac sand”) is used to hold open the cracks and fissures created by hydraulic pressure. Each stage of the process requires hundreds of thousands of pounds of quartz-containing sand; millions of pounds may be needed overall. The mechanical handling of frac sand creates respirable crystalline silica dust.

In 2012, researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) collected 111 personal breathing zone samples at 11 sites in 5 states to evaluate worker exposures to respirable crystalline silica during fracking. At each of the sites, full-shift samples exceeded occupational health criteria, in some cases by 10 or more times — in one case, by 100 times.

OSHA now proposes new standards for exposure that cut current permissible exposure limits (PELs) in half. According to the OSHA FactSheet, the current PELs for crystalline silica were researched in the 1960s, adopted in 1971 and not updated since that time. They don’t adequately protect workers; they are outdated, inconsistent and hard to understand. The proposed regulations also mandate several new workplace controls, among them limiting workers’ access to areas where silica exposures are high and providing medical exams to workers with high silica exposures.

The proposed rule is expected to prevent thousands of deaths from silicosis, lung cancer, other respiratory diseases, and kidney disease. OSHA estimates that, once fully realized, the new standards will save nearly 700 lives and prevent 1,600 new cases of silicosis per year. It is especially relevant to companies involved in fracking: Approximately 25,440 oil and gas workers are currently exposed to silica dust and 16,056 are exposed to levels above the proposed new PEL of 50 micrograms per cubic meter.

Industry has vigorously opposed a new standard, especially lowering the PEL, arguing that the agency should focus on enforcing the current limit rather than setting a lower level. Public hearings were scheduled to begin on March 18, 2014 in Washington, D.C.

But new standards, like the current ones, are meaningless without enforcement — and West Virginia’s record in that area is appalling. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, deaths from silicosis declined 93 percent from 1968 through 2002 and even more since then. But, natural gas fracking has virtually (and literally) exploded in West Virginia and around the country in just the past few years.

Acute silicosis, such as afflicted the Hawk’s Nest workers, is caused by heavy exposure to crystalline silica over a short time, and its incubation period is a matter of months. However, simple silicosis can remain latent for 10 years or more. Given the rapidly increasing ranks of well workers exposed — and many far over-exposed — to crystalline silica, that fact is truly frightening. If measures aren’t taken to protect these workers now, another enormous tragedy is likely lurking in our future.