A guest blog from Dr. Stephen T. Young and Dr. Brian Pitman

With the Democratic debates in Detroit, one might have expected that the Flint water crisis to be a topic of conversation. The best quote of the night on this subject likely came from Marianne Williamson, who said, “Flint is just the tip of the iceberg. …this is part of the dark underbelly of American society… It’s bigger than Flint. It’s all over this country. It’s particularly people of color. It’s particularly people who do not have the money to fight back.”

Ms. Williamson is right. Many communities over the last decade have been stripped of access to clean water. Yet, the federal, state, and local governments have failed to act, acted negligently and/or acted criminally in many communities when it comes to water infrastructure and distribution.

Mingo County, WV. Photo by Vivian Stockman

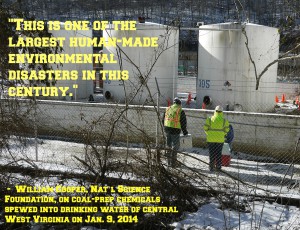

Another community with an evolving water crisis is West Virginia. People in the state are facing serious health hazards as companies and profit receive precedent over the people and their access to water, something that is not a new experience for West Virginians. The state has an often-ignored history of similar harms due to their “disposable” construction in society and once again they face environmental and health related dangers.

In 2018, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) released a proposal requesting updates to nearly 60 water quality standards based on the 2015 recommendations of the Environmental Protection Agency. This included drastically decreasing river and stream pollution. However, West Virginian legislators ignored these proposals and refuse to repeal many laws in place allowing industries to “dump” waste with little oversight. In fact, they have only enabled private industries to pollute further the water going to West Virginian homes. In March 2019, the West Virginia House of Delegates passed a bill rejecting the updated EPA human health water quality standards.

One might ask why they rejected these standards or may wonder the rationale of private industries for rejecting this proposal. Well, a representative from the West Virginia Manufacturing Association argued that there is no need to adhere to the provisions because West Virginians drink less water, consume less fish, and are heavier than the national average. This rhetoric plays on tropes of laziness, unhealthiness, and hygiene often used to depict West Virginians as “trash” to rationalize the economic exploitation of the people who occupy the land.

Again, this is not a new phenomenon in the United States or in West Virginia. West Virginia residents sit on the periphery of the broader capitalist economy due to the perceptions and exploitation of the region. Specifically, the area continues to experience the ramifications of historical market fluctuations as a response to demographic, technological, and resource change that situates metropolitan areas as the predominant center of capital development. This peripheral status ingrains the economy within a broader precarious position in society, further exacerbating issues seen with industrial decline and increasing poverty levels that allow for “solutions” centered on diminishing regulations to “draw in” or retain damaging extractive industries.

Additionally, citizens of West Virginia receive different treatment based on their overall construction in broader society. An enormous wealth of research exists discussing the creations of Appalachians as lazy, uneducated, and dangerous. These tropes are not relegated to Appalachians, but to rural people and areas (see Vox’s David Roberts’ Twitter thread). All of these tropes support their position as worthy of exploitation.

Historical creations of the “filthy hillbilly” continually morph to suit the current stereotypes of the “backwoods inbred” roaming through the rural scenery of the state. We see this through the fascination with the infamous Jesco White and other “pop” culture obsessions playing on modern representations of the Jukes and Kallikaks. The fact that West Virginia already exists in the societal imagination as disposable supports the broader rationale discussed by the West Virginia Manufacturing Associations representative. West Virginians do not exist in the same classification as “pure” and still fall victim to the white trash trope used against earlier generations of “less than white” immigrants from European countries.

We must be the catalyst to ensure that clean water becomes a focal point of the 2020 presidential campaign. As was on display in Wednesday night’s debate, only two questions were devoted to the water crisis only an hour’s drive away from the stage, before CNN moderators changed the subject. Unfortunately, the burden is on the people to prioritize clean water as the candidates’ campaign to become the next President of the United States.

Dr. Stephen T. Young is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Marshall University. Dr. Brian Pitman is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Pacific Lutheran University.

We all need clean water, and the candidates should be addressing this issue. Get out there with your clean water questions to bird-dog those campaign events, be they in person or online.