I spent the day of January 9, 2014, at the Beckley Veterans Affairs hospital with my father, learning that there would be no treatment for his cancer and he had maybe weeks left. We were completely unaware of the events unfolding on the Elk River in Charleston.

We made the hour and a half trek back to my father’s home, and prepare to settle him in to rest. The trip to the VA and back was painful and exhausting for him: he was still recovering from the major surgery he had in December. That surgery was to have removed his cancer, but it was unsuccessful. We were running water to get dad cleaned up and ready for bed when a friend of the family burst through the door. “Do not use the water!” he shouted, “there has been some type of spill in Charleston.” Hoping it was an overreaction to something, I turned on the TV. My heart sank.

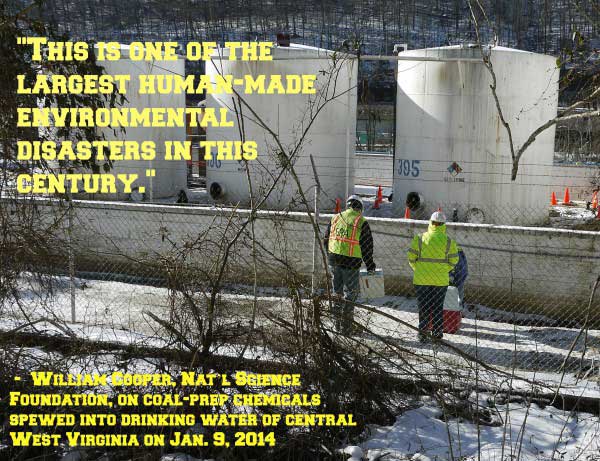

Through my work as a volunteer and then on staff with OVEC, I was well aware of water issues in the region. For many communities, pollution in their water from industry was a daily occurrence. But what I saw was the consummation of all my fears. We were under a state of emergency. A petrochemical used by the coal industry known as crude 4-methylcyclohexanemethanol (or MCHM) had leaked from its holding tank above the public water intake of nine West Virginia counties, serving about 300,000 residents.

Little was known about the chemical at first. As the situation progressed it became obvious that it would be days before we could use our water for anything more than flushing toilets. It was utter chaos. Regulators and government officials would tell us one thing, then another. No one knew the health impacts of MCHM because the MSDS sheet was virtually blank. We had all become test subjects of an unknown petrochemical. People were getting sick. Water disappeared from the shelves of local stores within hours and it would take some time before relief water would come into the region from the National Guard and others. Days without water would turn into weeks. This time is now known as the WV Water Crisis, or #wvwatercrisis.

I would spend the next several days melting snow and boiling creek water to take care of my dying dad; watching from his bedside as crisis unfolded.

It has only been five years since one of the greatest chemical disasters this side of the new millennium happened right here in our region. So it is sheer insanity to me that they are now planning a 400-plus mile petrochemical mega-complex (the Appalachian Storage and Trading Hub) for the Ohio and Kanawha river valleys. Rather than one chemical tank sitting one mile above a public water intake for 300,000 people, we could have massive petrochemical infrastructure upstream of public water intakes of five million people. This benignly named Hub would include underground storage of hazardous liquids in unlined geological formation, which if permitted could create a huge potential for contamination of groundwater. The Hub would also mean a massive increase in the amount of fracking that is already harming water systems. If the WV DEP could not regulate one chemical storage tank, how in the world can they regulate all the infrastructure of a 400-mile-long petrochemical complex? Even as you read this, our state and federal governments are actively working to gut clean water protections to ensure something like the MCHM spill will happen again. We are not safe.

We were lucky in the fact that MCHM had an odor, altering people that something wrong was going on. Many petrochemicals have no color, taste, or smell. Most are proprietary. And if you thought methylcyclohexanemethanol was hard to say, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of chemicals that would be refined as part of this Hub that are even harder to say. That’s hardly the issue of course. One top issue is the health impacts.

This proposed petrochemical complex threatens the water of more than five million people; that’s the real rub! It’s not a matter of if, but when something goes wrong. Even the MCHM crisis aside, West Virginia has already had a very long history of industrial disasters. Don’t we deserve better than that? Haven’t we learned our lessons yet?

My father, a retired coal miner and Vietnam Vet, spent some of the last weeks of his life without access to water because of a petrochemical. No one should come into this world or leave it without the promise of clean water. What happened on the Elk River in 2014 can happen again, especially if the state allows the construction of the Appalachian petrochemical complex.

In reflecting upon the five-year anniversary of the MCHM spill, I am thankful for the unsung heroes who endured that crisis. There were the hundreds of people who stepped up to donate money and/or volunteer time to distribute clean water and supplies to people living in the more rural areas impacted by the spill. Many braved long trips and long hours in cold weather to go into communities and hand out supplies in areas underserved by the National Guard and Red Cross. An amazing network of grassroots organizations and community members came together, providing aid to those in out-lying areas. Through the use of phone calls and social media, with groups like the WV Clean Water Hub, they were able to identify areas and get boots on the ground before the government agencies could even respond. It’s these stories that are often left out of the narrative of the water crisis.

Through mine and OVEC’s involvement in relief efforts, my father was able to see the wonderful work those people did. I know he was both thankful and proud of them. We must pray the day never comes when we have to do that kind of work again. We must stop the destruction of our life giving water for profit. For it truly is water that unites us all.