This was the talk that Dr. Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, was to have delivered the keynote speech at OVEC’s annual meeting and Treehuggers’ Ball on September 15, 2018. She also recently published, as co-editor, 55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike.

Hurricane Florence prevented Dr. Catte from joining us, but she e-mailed us her talk:

Good afternoon. I’m happy to join you here in Huntington and help kick of this meeting. Some of you might know me as a writer, but what you probably didn’t know is that I’m also a time traveler. I’ve seen Appalachia’s future, and OVEC asked me to tell you about it.

In 2016, my partner Josh and I moved to the Beaumont/Port Arthur area of Texas, on the Gulf Coast. A university made Josh and job offer and off we went, because we’re both historians and it’s hard to find work.

Now, we both knew about the Gulf Coast petrochemical industry in the abstract, and we weighed what we thought we knew against what we’d experienced here, in Appalachia. Both of our families are from southwestern Virginia, which is the state’s coal country. And I think we both thought, “Well, how can anything be worse than coal?”

Living in Appalachia, I think, our vantage point to environmental destruction is hard earned. We see things that are impossible to unsee, and undo. It’s hard to imagine ruin that doesn’t look like what is all around us, because there’s so much. Larry Gibson said, “This is what the end of the world looks like to me,” and I believed him.

And so it can be jarring when you encounter the end of the world somewhere else, too.

I want to tell you about encountering that in Port Arthur, Texas. Because I believe the future that West Virginia’s state officials, investors, and engineers want—an Appalachian fracked gas and petrochemical hub—is already there.

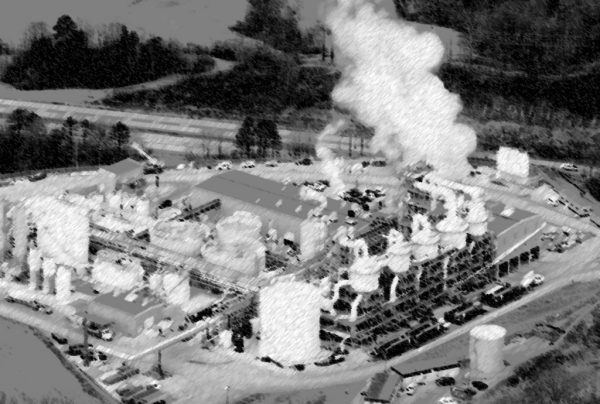

Port Arthur is located 90 miles east of Houston. Texas, of course, is the leading crude-oil and natural gas producer in the nation. Port Arthur is home to four major oil refineries, owned by Valero, Motiva, and Exxon. The Motiva refinery is likely the largest in the nation. It produces 600,000 barrels of crude oil per day, and that clocks up to almost a million if we count the other refineries.

In addition to this, there are five petrochemical plants, one petroleum coke plant, and an international chemical waste incineration facility. When Hilton Kelley, an environmental activist and lifelong resident of Port Arthur, drew attention to the fact that two million gallons of VX hydrolysate, a by-product created during nerve-gas processing, had been incinerated without any means to measure emissions of the chemical, his own mayor called him “a clown and a loser.” Hilton Kelley won the Goldman Prize three years later.

And, to add insult to all of this, Port Arthur is also a hub of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, whose fate remains unclear at the moment.

It is the most humid city in the United States, home to 6 superfund sites. In 2010, an Exxon-chartered tanker spilled 462,000 gallons of crude oil into the nearby Sabine-Neches canal.

Many communities in Port Arthur – which has a population of around 55 thousand and is predominately African American – are what are known as “fence line” communities. This means they’re directly in the path of contamination from nearby refineries, often from ‘invisible’ emissions.

One in five household members suffers from a serious respiratory illness, the cancer rate is twenty-five times higher than the state’s average. One refinery fire, which occur often, can release as much as 120,000 pounds of volatile compounds.

And there are few economic rewards for those who remain. The unemployment rate is over 15%, and those who can or do work only earn half of what the average Texan makes. Some plants and refineries don’t even invest in required infrastructure, like an independent power grid, and blackouts occur often.

Port Arthur is also a case study in white flight. Since the 1980s certainly if not before, Port Arthur has experienced the depopulation trifecta of racism, industrial contamination, and natural disasters. Hurricane Ike, in 2008, and last year’s Hurricane Harvey hit the area hard. It shouldn’t surprise you that state and federal agencies have drug their heels in helping rebuild a community of mostly poor, black residents.

That’s Port Arthur at a glance. What this snapshot doesn’t and can’t capture is the physical reality of living in that space.

Here’s an exchange I will never forget. Shortly after we arrived in Texas, just weeks into our new life, one of Josh’s colleagues and his wife invited us out, to give us the lay of the land.

Once small talk ended, he asked us if we were old enough to remember the Gulf War. We answered we were kids, but as historians we were of course familiar with it. But what he was asking, in a roundabout way, was if we knew what burning oil and gas flares looked like. In 2016 EPA had – and I have no idea such a program still exists and if so, how much longer it will continue to survive under Trump – something called a toxic release inventory, which records events when emissions exceed safe levels. There were 2,500 such events in Texas the year I lived there, and Jefferson County – our country – was the worst.

We were told to expect such events often, but that Josh was fortunate because his office and department did not face the refineries. This meant the paint on the walls wouldn’t melt as fast. Strange that no one mentioned any of these “quirks” during the interview process.

Orange fire, and thick black smoke. This might happen for an hour straight, maybe longer. It’s just a thing that happens if power is momentarily lost or a system fails. The area was once called the Golden Triangle because of the enormous concentration of wealth, but the name sticks despite downturns because, from above, it looks like the world is on fire. Because it is.

There is no direction in which one can travel for 100 miles and be free of the sight of leviathan nightmare. Towers rising on towers, aflame, valves, pipelines, fences. Sodium vapor lights, guard posts. Smoke of every color and hue, cranes depositing barrels and waste bound for shipping channels.

If you are on the road when there’s a shift change, you will also see taillights. Those who can afford to live elsewhere do so, in cities like Winnie or Nederland or Vidor, where the population is almost 90% white, a phenomenon that does not and should not occur in Texas without a history of violence, intimidation, and calculated inequality. These cities are but 6 to 10 miles downwind, but every mile counts when proximity is connected to risk of cancer.

This means much of Port Arthur is a ghost town, made up of vacant lots and dilapidated buildings. Yellow caution tape covers the downtown area, alerting pedestrians to rebar and concrete that has fallen from buildings onto the sidewalks below. Port Arthur was once one of the most vibrant cities on the gulf, one that could give New Orleans a run for its money, particularly in number of black-owned businesses and night clubs.

And as you are taking this ruin in, you will likely be surveying all through burning, stinging eyes. The smell is indescribable. The major notes are sulfur and methane, with a rot so deep that I would sometimes spontaneously vomit. There was no such thing as fresh air. Even on those magical days when the wind was whipping in the right direction the smell of dry rot and mold was still overwhelming, from layers of storm damage and neglect.

There was a warning system in place, like how we get flash flood warnings, to warn us of “adverse odors.” You could tell how long someone had been living in the triangle by the ability to smell. Do they still have it? Then they’re likely newcomers, like Josh and I were. When we moved back to Virginia, we had to throw away most of our clothes and soft goods, like our bed, and sofa. Everything we owned was impregnated with the smell of refineries. We were poor but we tried hard and suddenly we became people who did not deserve fresh air. Again.

In Port Arthur, there’s a housing development just yards away from the Valero and Motiva refineries, Carver Terrace. One of the sights that’s seared into my memory is a playground within eye-line of those refineries, with exposed pipes snaking through it, bursting up through the ground, with warnings about hydrocarbon gasses hanging from a fence that was just yards away.

The people living in Carver Terrace have likely since relocated to new homes further away from the refineries but that plan almost stalled because the developer asked for a $10,000 tax credit from the community. “We can’t continue giving out tax credits,” the city council said, at the same time that it allowed Motiva to carry a tax abatement that cost their schools $3.6 million annually. The accents might be different but people in Texas sound a lot like people in West Virginia.

And so my partner and I decided to leave. We’d left the state for the first time in four months to go to a conference and we could suddenly breathe, and my head stopped hurting. It took us many, many more months before we could save the money and find jobs back home, though. A fun fact is that I wrote my book cycling between my bedroom and our closet because the latter didn’t have ventilation and during ‘adverse odor’ events, it was the place to be.

So we left, and I imagine that it cost us about $15,000 to get out of dodge, from out of pocket moving expenses, replacing furniture and clothing, and then the under and unemployment we had to build back up from. And I mention this because there was a popular article in the National Review about 3 years ago, casting Appalachia as a white ghetto, that spent about 4,000 words milking every vulgar stereotype before concluding that the people of Appalachia, at least those of us worth saving, just need U-Hauls. That’s the conventional wisdom, right? If you don’t like what’s going on around you, you can just move somewhere else.

This logic really haunts me, this idea that on very rare occasions innocent people just need to “make way” for progress. That some places just can’t be saved. That maybe they’ll be better off if something forces them into a more suitable environment. Because there’s not a single instance where a greedy person hasn’t looked at the land in Appalachia and tried to use that excuse. Not a single instance. Not in the realm of coal, and timber. Not even in the world of outdoor recreation. Not even in the realm of rural development. Not even under the gaze of white settlers who forced indigenous people from the land.

So we submitted to this logic, because there was nothing to be done. We didn’t know how power worked in Texas, we couldn’t afford to get ill, and to be honest, neither one of us wanted to work for a university that wanted sixteen different kinds of background and reference checks on their candidates but didn’t think it necessary to disclose that you’d be working 500 yards from an oil refinery that often caught on fire.

Bad luck, for us. But according to all the logic of big business and progress this is a one time sacrifice, right? Except that was number two for us.

And there was to be a third. We happened to move to Augusta County, Virginia, where Duke and Dominion energy have partnered to build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline – a completely unnecessary project that has no value to the public whatsoever, will cost ratepayers around 2.3 billion dollars, has deprived hundreds of property, burdened families with legal bills, and will destroy the most chilling inventory of sacred and historical landscapes.

It will use experimental and untested compression technology – and those compressor hubs are going to be located in poor African American communities, naturally – and all of this has taken place under the leadership of two Democratic governors who have made environmental and green issues a cornerstone of their campaign and have fought tirelessly to block destructive projects in their own backyard.

All throughout summer, fall, and winter, when Virginia wasn’t getting invaded by Nazis, it was getting invaded by out of state contractors and energy company goons, who had convinced all the state park folks – the pipeline crosses the Appalachian trail – that they were real live cowboys and could zip all over the place in ATVs writing trespassing summonses for campers and hikers.

We had Red Terry and her daughter Minor in a tree-sit for over two months outside their home, and half a dozen or so anonymous sitters in monopods on public land for weeks at a time as well. We had grandmothers and college professors chained to construction equipment, and a state government investigating our local Sierra Club for terrorist activities. Strangely, being labelled a terrorist by the governor’s spokesperson hasn’t stopped either political party from soliciting me non-stop for donations, which you would think they’d want to be careful about if people like me are as bad as they say.

So where are people like me, and people like you, supposed to go? Where is the statehouse free of politicians that won’t sell me out to an energy company or developer? Where can I live where I won’t have to worry about a corporation using eminent domain to send me somewhere else? Where’s that magical place where corporations pay their tax burdens, whether that corporation is Amazon, or Apple, or Dominion Energy, or something owned by Jim Justice.

In Virginia, for example, Amazon has data centers and Dominion Energy, which powers these data centers, cuts Amazon a special retail rate and passes on its loss to ratepayers. Tell me where I can go where I will not be at the mercy of a titanic industry? Politicians and developers in Appalachia tell us that industry is freedom, that when industry thrives we all do, but we know that isn’t true. When industry thrives we are poisoned, plundered, vanished, separated from our families. That is the opposite of freedom.

Appalachia’s, and particularly West Virginia’s, political and industry leaders want to transform the region into a petrochemical storage hub, much like the Gulf Coast. In May 2017, the American Chemical Industry released a press release that said, “The Appalachian Region is an ideal location for the emergence of a second major petrochemical manufacturing hub in the United States, offering benefits such as proximity to abundant natural gas liquids from the Marcellus/Utica and Rogersville Shale formations that could feed at least half a dozen world-scale petrochemical complexes in addition to a number of smaller facilities.”

In November 2017, Jim Justice signed an $83 billion dollar memorandum of understanding with Chinese corporations to make the petrochemical hub a reality in West Virginia.

This specific arrangement now appears to be on the skids in part thanks to Trump’s trade war with China but also a lot of incompetence and corruption among West Virginia leaders who can’t even handle flood recovery money, let alone a multi-billion dollar international investment. But these set backs, which we should all take delight in because if nothing else they are very embarrassing for bad people, don’t mean that the vision of the future held by power players has changed.

And because I know how this could end – I’ve lived it — I want to encourage each one of you to fight this future with all you have. I will leave the “how” of the fight to OVEC, who have opposed this reality since it was the twinkle in the eye of a low-life politician, but don’t be like me and assume that things can’t get any worse, because they can.

The only chance we have is to fight for each other, which means that I will fight for you but also people who live in places like Port Arthur, and I will see how our fates are connected and instead of letting that terrify me I will let it expand my definition of what and who my community is and that is powerful.

Earlier I asked where we could go to experience freedom, where we could find politicians who won’t sell us out and industries that aren’t scheming for to enrich themselves at our expense, and at the expense of the land. Where can we go where our lives have value, where we’re allowed dignity, where we might envision a better future?

For now, it isn’t a place, but a movement. A movement that fights for the person across the world just as hard as the person next door. A movement that fights for the sick, for the elderly, and for the person not even born, so that their struggles might be fewer than ours. A movement that understands loss, but also resurrection.

If you have been fighting this fight for decades, as OVEC has, thank you. You have saved land, and people. You have created a healthier region. You have defied some of the most powerful corporations in the world. I read something very beautiful that Aaron wrote for his mother Dianne, your founder, and he said. “Her accomplishments can be measured in what is absent. There is no pulp mill in Apple Grove. There is no BASF refinery in a low-income community near Huntington. There are mountaintop mines that never happened. And whether they know it or not, the people of the region breathe easier and drink clean water because of the life my mother lived and the work she did. There are cancers whose absence no one will know to thank her for.”

And if you are new to the movement, that is okay, too. Martin Luther King said “In the unfolding conundrum of life and history there is no such thing as being too late.” Being a little late is always better than not knowing that there are no jobs on a dead planet, and that all the corporate growth in the world won’t make a difference without clean water and air.

Take good care of each other, and thank you for letting me join you this evening as you start a new season. Hang in there. I believe that we will win.